Different Breeds of Wagyu

Wagyu cattle originated from native Japanese breeds, which have evolved by adapting to Japan’s unique climate and environment. Since the modern beef-eating culture started to flourish in Japan in the 1860s, Wagyu has been improved to produce higher-quality beef to satisfy the taste preferences of Japanese consumers.

The most noticeable characteristic of Wagyu beef is its intense marbling. The high intramuscular fat (IMF) content improves the texture, juiciness, and palatability. The specifics can vary by location. Japan produced the first wagyu beef, which remains the gold standard. Japanese wagyu must come from one of four native cattle breeds:

Kuroge Washu

(Japanese Black)

Akage Washu

(Japanese Brown/Red)

Nihon Tankaku Washu

(Japanese Shorthorn)

Mukaku Washu

(Japanese Shorthorn)

Wagyu, which encompasses four Japanese beef breeds, is predominantly represented by the Japanese Black breed, constituting approximately 97% of Wagyu in Japan (MAFF, Production, Marketing and Consumption Statistics Division, 2015).

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, for beef to be labeled as “Wagyu” in the US, the animal must be an offspring of:

- A registered sire of at least 15/16 or 93.75% Wagyu blood (i.e. Fullblood or Purebred) or;

- A registered dam of at least 15/16 or 93.75% Wagyu blood (i.e. Fullblood or Purebred);

4 Major Breeds of Wagyu

Japanese Black (Kuroge Washu)

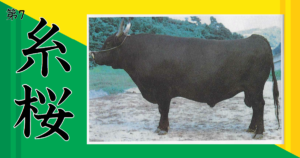

Japanese Black, also called Kuroge or Kuro, is the best Wagyu beef that can be made in Japan. Coming from the Chugoku area, it has won much praise for being of the highest quality and great flavors. Because of the breed’s popularity, a registration group was set up in 1948. This has made it easier to breed and improve the breed over the years (Wagyu Registry group, 2002). The Japanese Black breed is striking, with its unique brownish-black hair, gray skin, and black muzzles and feet. This breed is special not only because of its appearance but also because it is known for being calm, making it easy for farmers to handle. However, its high level of marbling and exceptionally soft meat may be its most renowned trait. These qualities help to create an exquisite taste profile.

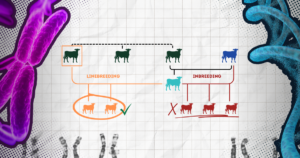

There are three main blood types that Japanese Black usually comes from: the Tajima strain from Hyogo Prefecture, the Kedaka strain from Tottori Prefecture, and the Itozakura strain from Shimane Prefecture. These types were carefully chosen and bred with other generations to improve traits like marbling and the quality of meat people want. Because of this, the fat in the rib eye area of Japanese Black can sometimes be more than 50%, which means it is vibrant (Oyama, 2011). Even though Japanese Black is the most popular breed for making Wagyu, it is still changing. Scientists are working to improve its economic traits and genetic diversity. One cannot say enough about its importance in Japanese food; it is still a sign of culture and great cooking. (Motoyama et al., 2016)

Japanese Brown/Red (Akage Washu)

Japanese Brown, which is also called Akaushi, is one of Japan’s Wagyu breeds that is all its own. It might not have as much marbling as Japanese Black, but its unique traits make it appealing to picky eaters.

Japanese Brown/Red is mainly bred in Kumamoto, Kochi, and Hokkaido Prefectures. Its caramel-colored coat makes it stand out. The Simmental breed was made better by crossing it with the Akaushi breed, used as work cattle in the Meiji period. It was recognized in 1944 as Japanese-born beef cattle. One thing that makes it unique is that it has less fat, about 12% or less. It tastes great and has a nice, hard body because it has a lot of lean meat. Many people are interested in it because it is healthy and it has a mild flavor. Its fat is slightly less marbled. (Motoyama et al., 2016)

Japanese Shorthorn (Nihon Tankaku Washu)

The Nihon Tankaku Washu, or Japanese Shorthorn, shows how well Wagyu breeds can adapt to different temperatures and settings. This breed has made a name for itself with its unique traits. It is mainly raised in northern Japan, in places like Iwate, Aomori, Akita, and Hokkaido Prefectures.

With a reddish-brown body, the Japanese Shorthorn may not have as much coloring as the Japanese Black, but it makes up for it in other ways. Nambu-ushi, a breed from Iwate Prefecture, is thought to have been the ancestor of the Japanese Shorthorn. It gave the breed solid legs and feet and the ability to do well in colder areas. One great thing about the Japanese Shorthorn is that it makes milk and uses roughage efficiently, which makes it a good choice for grazing. It might not sell for as much as Japanese Black on the market, but its variety and adaptability have ensured that it will stay in Japan’s beef business. (Motoyama et al., 2016)

Japanese polled (Mukaku Washu)

Japanese Polled, which comes from Yamaguchi Prefecture, is a pretty interesting comparison to Wagyu. Japanese Polled has a darker coat than Japanese Black, giving it a unique look. However, it has less patterning than Japanese Black.

In 1966, the first national competition for Wagyu meat production took place. The Japanese Polled stood out because it had the perfect body measures and gained weight quickly, making many people think it would be a good beef breed. However, there are still few; only about 200 are bred and raised in Yamaguchi Prefecture. Even though it has problems, Japanese Polled is an integral part of Wagyu history and shows Japan’s different beef types. In terms of marbling, it might not get as dark as Japanese Black, but its unique qualities and room for growth show how Wagyu in Japan is still changing. (Motoyama et al., 2016)

Historical Origins of these Breeds

Meiji Period (1868-1912)

During the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government aimed to adopt Western food habits and culture, increasing animal product consumption. To enhance local breeds, the government imported foreign animals for breeding. About 65% of imports were for pure breeding, while 35% were bulls for crossing with native cattle.

Despite initial reluctance from farmers, crossbreeding became common due to high market prices. However, by 1910, the value of crossbreds plummeted due to inferior working performance. This caused panic among farmers, leading to a halt in crossbreeding. The practice lacked clear objectives and resulted in undesirable traits. Although some improvements were seen in size and milk production, meat quality suffered. Various breeds were introduced inconsistently, with unclear selection criteria, leading to disparate outcomes across regions.

At the outset of the Meiji Period, cattle farming in Miyagi Prefecture predominantly involved native Japanese breeds. These cattle were primarily utilized as draft animals for agricultural tasks, such as plowing fields and transporting goods, reflecting traditional farming practices.

Efforts to improve cattle breeds were initiated by introducing Western cattle breeds renowned for their meat and dairy production capabilities. This introduction aimed to enhance the overall quality and productivity of the local cattle population, marking a significant shift in breeding strategies.

Concurrently, initiatives were launched to promote modern farming techniques, including the adoption of horse-plowing methods. This transition aimed to increase agricultural efficiency and productivity, laying the foundation for mechanized farming practices in subsequent periods.

The Meiji Period witnessed the establishment of institutions such as breeding stockyards and cattle farming associations. These organizations played pivotal roles in promoting selective breeding, improving livestock quality, and disseminating agricultural knowledge among farmers.

Beef production during the Meiji Period saw fluctuations in response to military demand during conflicts such as the Sino-Japanese War. Increased demand for beef for military rations led to concerns about declining cattle populations, prompting strategic breeding programs to ensure sufficient supply.

By the late Meiji Period, government policies increasingly emphasized progressive breeding practices with Western cattle breeds. These policies aimed to gradually improve domestic breeds by incorporating desirable traits from imported breeds, reflecting a strategic approach to livestock development.

Taisho Period (1912-1926)

Compared to the preceding Meiji Period, the Taisho Period witnessed a notable expansion in the cattle population in Miyagi Prefecture. This increase was attributed to improved breeding practices, better animal husbandry techniques, and a growing emphasis on agricultural development.

A significant development during the Taisho Period was the introduction and promotion of hybrid cattle breeds. These mixed breeds were created by crossing native Japanese cattle with imported Western breeds, aiming to combine desirable traits such as meat quality, milk production, and disease resistance.

During the Taisho Period, cattle breeding clubs and cooperatives were formed. These groups were significant in promoting selective breeding, improving the quality of animals, and teaching farmers about farming. These groups helped farmers by giving them support, resources, and advice, which led to improvements in breeding methods and genetic selection.

Native Japanese cow breeds were still promoted and used during the Taisho Period, even with the advent of hybrid breeds. These varieties were highly prized for their ability to adjust to local environmental circumstances, their durability, and their compatibility with traditional agricultural methods.

Due to shifting dietary habits and rising demand for beef, the Taisho Period saw an increase in the concentration on meat production. To satisfy changing customer demands, efforts were undertaken to raise carcass yields, optimize production processes, and increase the quality of meat.

The Taisho Period marked a growing focus on meat production, driven by increasing demand for beef and changing dietary preferences. Efforts were made to improve meat quality, enhance carcass yields, and optimize production systems to meet the evolving needs of consumers. Technological advancements, such as improved veterinary care, disease control measures, and feed formulations, enhanced productivity and efficiency in cattle farming operations during the Taisho Period.

Showa Period (1926-1945)

The early Showa Period was characterized by economic challenges, including the Great Depression, significantly impacting Miyagi Prefecture’s agriculture. Despite these challenges, efforts were made to modernize agricultural practices, including cattle farming. The government introduced various initiatives to support agricultural development, increase food production, and modernize farming practices. This included subsidies, technical assistance, and infrastructure projects aimed at enhancing the efficiency and productivity of cattle farming.

Technological advancements were crucial in transforming cattle farming during the Showa Period. Improved breeding techniques, veterinary care, disease control measures, and feed formulations contributed to increased productivity and efficiency in cattle farming operations.

The Showa Period saw the introduction of new cattle breeds to Miyagi Prefecture, selected for their superior meat quality, adaptability, and suitability for mechanized farming practices. Selective breeding programs aimed at developing breeds with desirable traits further enhanced genetic diversity and productivity.

World events, such as World War II, significantly impacted cattle farming in Miyagi Prefecture. The demand for beef fluctuated in response to wartime needs, and agricultural resources were redirected to support the war effort, leading to changes in production patterns and priorities.

Conclusion

Wagyu cattle, originating from native Japanese breeds, have evolved to produce high-quality beef, with intense marbling being a hallmark characteristic. The Wagyu designation is strictly regulated, requiring adherence to specific criteria regarding breed and origin to ensure authenticity.

Among the four major breeds of Wagyu, Japanese Black stands out as the most renowned for its exceptional marbling and meat quality, followed by Japanese Brown, Japanese Shorthorn, and Japanese Polled, each offering unique traits and flavors. The historical development of Wagyu breeds reflects Japan’s efforts to adapt to changing agricultural practices and consumer demands, with periods such as Meiji, Taisho, and Showa witnessing significant advancements in breeding techniques, the introduction of hybrid breeds, and the modernization of farming practices.

Despite economic downturns and wartime disruptions, Wagyu cattle farming has persevered, showcasing resilience and a commitment to preserving Japan’s rich culinary heritage.

References

Japan Livestock Industry Association (2015). Introduction to the universal Wagyu mark. http://jlia.lin.gr.jp/wagyu/eng/aboutmark1.html

Namikawa K. (2018) Breeding history of Japanese beef cattle and preservation of genetic resources as economic farm animals. Wagyu Registry Association. Retrieved from https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/386/2016/08/BreedingHistoryofJapaneseBeefCattle.pdf.

Motoyama, M., Sasaki, K., & Watanabe, A. (2016, October). Wagyu and the factors contributing to its beef quality: A Japanese industry overview. Meat Science, 120, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.04.026

MAFF, & Committee on Indication of Meat (2007). Guidelines for indicating distinctive meat such as Wagyu beefv/j/study/katiku_iden/06/pdf/ref_ data2.pdf

MAFF, & Production, Marketing and Consumption Statistics Division (2015v). Livestock survey. http://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/tikusan/index.html (Retrieved: 10 January 2016.

Namikawa K. (2018) Breeding history of Japanese beef cattle and preservation of genetic resources as economic farm animals. Wagyu Registry Association. Retrieved from https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/386/2016/08/BreedingHistoryofJapaneseBeefCattle.pdf.

Wagyu Registry Association (2002). Practice of the registration inspection and registration examination. (Retrieved 11 January 2016) http://cgi3.zwtk.or.jp/?page_id= 1262