Types of Artificial Insemination

Table of Contents

When working with reproduction methods in bovine, there are Various methods available for enhancing Wagyu cattle reproduction, including specialized techniques such as artificial insemination (AI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), and embryo transfer (ET).

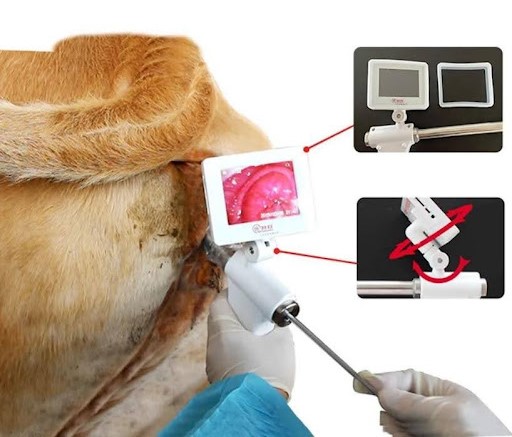

Using advanced equipment, semen containing live sperm cells is meticulously collected from superior Wagyu sires and introduced into the reproductive tract of Wagyu cows during AI procedures. This process involves precisely inserting a portion of the semen, either diluted or directly collected, into the cervix or uterus of the female at optimal timing and under stringent hygienic conditions. Artificial insemination serves as a pivotal tool not only for facilitating impregnation in Wagyu cattle but also for genetic enhancement and gender selection using sexed semen. These innovative methods play a crucial role in Wagyu breeding programs, allowing for the preservation and improvement of desirable traits, ultimately contributing to producing high-quality Wagyu beef and advancing the breed as a whole.

Artificial insemination is not merely a novel method of bringing about impregnation in cows. Instead, it’s a vital instrument primarily used for improving cattle and even selecting the gender of the offspring using sexed semen. Which then can be used for more efficient Farm management.

Methods for Artificial Insemination

Various AI techniques are utilized in Wagyu cow breeding, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses.

1. Vaginal Route

The vaginal route of artificial insemination involves depositing semen into the cranial part of the vagina without specifically targeting the cervix. This method requires minimal technical proficiency and handling facilities, making it relatively simple. However, it is not suitable for using stored semen due to the high number of spermatozoa required for each insemination. Despite its simplicity, conception rates are generally poor when used with pharmacological estrus synchronization, making it most effective during the natural breeding season. The ideal timing for insemination is before ovulation, typically 12 to 18 hours after the onset of estrus.

2. Intracervical Route

Intracervical insemination involves inserting the insemination catheter into the cervix, typically with the hindquarters of the heifers elevated. The depth of penetration into the cervix significantly influences conception rates, emphasizing the importance of technical proficiency. Although adequate conception rates can be achieved after estrus synchronization, they are generally lower compared to natural service or fresh semen insemination. The ideal timing for insemination is around 55 ± 1 hours after the removal of intravaginal progesterone inserts or 15 to 17 hours after the onset of detected estrus.

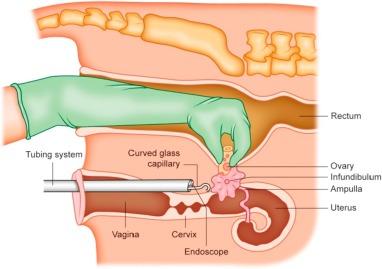

3. In-vitro Fertilization (IVF)

In cattle IVF, the process begins with selecting healthy donor cows and inducing superovulation if needed. Oocytes are then collected through OPU and evaluated for quality. Meanwhile, semen is collected, processed, and capacitated for fertilization. Oocytes are matured in vitro, followed by fertilization with prepared sperm. Embryos are cultured until the blastocyst stage, evaluated, and either transferred to recipient cows or cryopreserved. Pregnancy is monitored in recipients, and data on procedures and outcomes are recorded for analysis and improvement. Through meticulous execution of these steps, IVF in cattle contributes to genetic advancement and reproductive management in the industry.

4. Transcervical Route

Transcervical insemination is a newer method for intrauterine insemination via the cervical route. It involves fixing the cervix with forceps and introducing an insemination needle through its lumen. While this method can achieve better conception rates than conventional intracervical insemination, it is associated with significant levels of trauma to the cervix. Despite the potential for improved results with expertise, it is currently less favored compared to laparoscopic insemination due to its lower pregnancy rates and associated trauma.

5. Sexed Semen

Sexed semen technology aims to control the sex of offspring by separating X- and Y-bearing sperm. Flow cytometry has become a viable method for commercial sexing of semen. Previous attempts based on surface antigens or electrophoresis have been less successful. The current method relies on the difference in DNA mass between X- and Y-bearing sperm. DNA staining with a fluorescent dye enables sorting based on fluorescence intensity. Flow cytometry sorts spermatozoa by charging droplets containing X or Y sperm accordingly. Approximately 20% of spermatozoa are successfully sorted as X-bearing or Y-bearing, with the rest unidentified or dead. However, the process is slow and may impair sperm function due to various insults during separation. Chromatin abnormalities have been observed in sorted sperm, but the DNA stain used does not appear to cause mutagenic damage. Optimization of sorting conditions can reduce sperm losses.

Conclusion

Artificial insemination is a crucial technology that aids in impregnating females and transforming cow breeding methods. The agriculture business may improve cattle production and health by using artificial insemination procedures such vaginal, intracervical, IVF, and transcervical channels to access the better genetic features of elite bulls. Each approach has unique benefits and difficulties, but together they significantly contribute to genetic progress and reproductive control.

References

Semen Collection from Bulls. (n.d.). http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/reprod/semeneval/bull.html

Ferré, L., Kjelland, M., Strøbech, L., Hyttel, P., Mermillod, P., & Ross, P. (2020). Review: Recent advances in bovine in vitro embryo production: reproductive biotechnology history and methods. Animal, 14(5), 991–1004. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731119002775

Johnson LA, Welch GR. Theriogenology. 1999;52:1323–1413

Seidel GE, Garner DL. Reproduction. 2002;124:733–743